Matthew Mickletz and Rachael Arenstein, MuseumPests Working Group

Short presentations on IPM observations, research and developments are an integral part of the MuseumPests Working Group’s annual meeting. To expand participation and reach, the MP-WG is hosting its first Public Presentation Session on IPM in the cultural heritage community. We will offer a brief overview of the Working Group, our resources and how to get involved.

IPM IN PRACTICE

IPM at The Met During the Covid Lockdown

Michael Millican, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

When New York City Shutdown on March 11th, 2020 The Met’s Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program needed to continue as usual while adapting to sudden and unusual circumstances. Each Museum department has members dedicated to monitoring for pest activity. With most staff working from home, we developed a plan to monitor the 21 wings and 2.2 million square feet of the museum offices and galleries on a regular basis with limited resources. I was lucky to have the cooperation of The Museum’s Collections Emergency Team (CET), a group of 40 staff members who are specifically trained to collaboratively respond to collections emergencies across the Museum, our essential staff in the Buildings and Security Departments and our pest management vendors. The museum was split into thirds (South, Center, and North) and we tried to inspect the entire museum every week. In combination with regular building inspections by The CET and essential staff, we were able to maintain a robust pest monitoring, reporting, and response system from March through August, when the Museum reopened to the public on August 29th, 2020. This presentation will cover the steps The Met took to keep the IPM program running during the lockdown, the challenges we faced with drastic changes to the urban and built environment caused by the lockdown, the IPM lessons learned, and reflections on 6 months of isolated working conditions for museum staff essential to the IPM program.

The Impact of COVID-19 on the Integrated Pest Management Program at the Worcester Art Museum

Hae Min Park and Eliza Spaulding, Worcester Art Museum

The recently revitalized IPM program at the Worcester Art Museum is primarily overseen by conservators, registrars, facilities, and protective services staff. This collaborative, multi-departmental involvement ensured the continuation of the program, especially during the early months of the museum’s long-term closure between March and October 2020. This short presentation will review our original procedures for the program, first put into effect in early 2019, the practical adjustments made during the pandemic, and preliminary findings about the impact of the museum’s long-term closure on pests found. The presentation also will highlight the efficacy of Excel and Google Sheets as a recordkeeping tool to log, organize, and generate pest counts and reports per criteria. The presentation will conclude with a brief overview of how we are using our twenty-one months of data collected thus far for future preventive strategies.

The Mysterious Case of the Blue Feather: Keeping an Eye on Materials Approved for Museum Events

Julie McInnis, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Remember parties?? Last year, before the pandemic began, there was an art after-party in one of our museum spaces. Photos of the aftermath showed how truly wild it got – streamers strewn, confetti showered, and what appeared to be feathers scattered across the floor. Photo evidence made its way to Conservation, who, while hating to be party poopers, immediately spotted the probable feathers and sounded the alarm that high-risk (already prohibited) materials were brought into the museum space. Were they real feathers? The vendor said they weren’t, but our guts told us otherwise. Would we be able to confirm either way? All remnants of the party had already been cleaned up (or so we thought!). Thus began the Mysterious Case of the Blue Feather. Whether or not we had real feathers littering our museum space (in an area where webbing clothes moths had already been seen) was a roller coaster of a question that took many twists and turns and ultimately landed on showing us the importance of interdepartmental communication, strong museum policies, and frequent IPM staff outreach. One day museums and other cultural centers will have events again, and this mystery can be a reminder to others that no matter how careful and prepared you think your institution is to outside vendors and events, risks remain and vigilance is key.

An Efficient and Pest Resistant Storage System for Adult Odonata Specimens, With Application For Other Museum Collections

Claudia Copley, David C. A. Blades and Kasey Lee, Royal BC Museum

A system of storing adult Odonata (damselfly and dragonfly) specimens will be described and compared to existing storage systems. The major design innovation is the use of tongue and groove (“zipperlock”) resealable polyethylene envelopes manufactured to fit the standard index card and specimen arrangement currently used in major collections. Other design improvements include low-cost, adhesive-free specimen trays and glass-top drawers built to fit in standard-dimension Cornell insect cabinets. Sealing of the bottom of the drawers was another important pest management strategy employed after consultation with conservation staff as to which product was suitable. This system has applicability to other collections; examples include Lepidoptera and Archeology.

The Sports Collection of Sport Lisboa e Benfica

Ana Nascimento, Sport Lisboa e Benfica Cultural Heritage

The Estádio da Luz is the home of the sports club Sport Lisboa e Benfica and under its stands there is a well-kept treasure. In an area of 900 square meters (m²), around 35,000 objects are held for they are a part of Benfica’s material history. You may ask yourselves “How on earth’s is it possible for such a place to house 117 years of history?”, but it is true and that is a fact! The structure, completed in 2003 for the 2004 UEFA European Football Championship, is the current residence of the material assets of this centenary Club, objects associated with great historical moments and the athletic achievements of its athletes and teams. It was only 6 years after its completion, in 2009, that the Direction decided to approve the organization, study, preservation, and communication of this collection. What we found “was not for the faint of heart”, but the raw material was so extraordinary that we knew we were going to do a job worthy of pride. It was necessary to decontaminate, organize, do the inventory, and photograph everything to have a real perception of the Club’s heritage. The work was hard and intense but, 10 years later, we can safely say that the collection is stable and mainly safeguarded from any biological activity. How was this accomplished? How was everything kept “bug-free” for the last decade? This is the ultimate victory for the conservation team of the Storage, Conservation and Restoration Department and the prize is a safeguarded collection!

Potential Applications of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in Museum IPM

Elizabeth Salmon, UCLA

Integrated pest management (IPM) relies primarily on preventive and nontoxic measures to mitigate risks posed by insect pests to the longevity of cultural collections. Indigenous communities around the world have developed time-tested environment management methods based on their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), which include strategies to limit the destructive behaviors of insects. One example is neem (Azadirachta indica), an evergreen tree indigenous to the Indian subcontinent where it has long been utilized for its antibacterial and insect deterring properties. Recent scientific studies have confirmed its efficacy as an insect growth regulator (IGR) and antifeedant as well as its safety for human use. Yet, questions remain about how best to integrate this natural solution into a reliable collections care plan. TEK is a potential source of increasingly sustainable, accessible, and culturally relevant collections care solutions worth of the consideration of conservators. The goal of this study is to document current applications of traditional pest management solutions like neem and consider how they may be adapted as an additional tool to supplement existing museum IPM. This presentation is an introduction to planned doctoral research to be carried out in pursuit of a PhD in Conservation of Material Culture at UCLA.

RESOURCES

IPM, Protecting Our Cultural Heritage: A Survey of Collections Care Trends

Eric Breitung, Lisa Goldberg, Zoe Hughs, Suzanne Ryder, Julie Unruh, Joel Voron, MuseumPests Working Group

The MuseumPests Working Group conducted a survey in 2018 to gather information about current trends in resource allocation and operational practices in institutions aiming to monitor and manage pest activity. The survey was posted to several different listservs, receiving 377 responses primarily from the USA and Europe but reaching 5 continents. The survey data was evaluated using Survey Monkey’s innate analytics and Tableau, an open access data visualization program. Use of Tableau allowed us to pose various questions about the data by exposing relationships between the data sets. Using the survey data and this team will report on general outlines for worldwide and regional trends in museum pest control methods, budgetary and personnel parameters, and pest populations. This information will help us refine and define where work is needed in designing IPM solutions for the museum environments.

The Latin Bug: Launching MuseumPests.net en Español

Fabiana Portoni, Silvia Manrique, Jessica Lewinsky, Beatriz Haspo, Laura Garcia-Vedrenne, María Castañeda, Christian Untoiglich, Amparo Rueda, Sandra Joyce Ramirez, Armando Mendez, MuseumPests Working Group

We are excited to officially launch MuseumPests’ Spanish-language version. This project began slowly but peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown in 2020. The project brought together bilingual (Spanish-English) professionals who work on IPM in cultural institutions around the world, APOYOnline – Association for Heritage Preservation of the Americas and MuseumPests Working Group leaders, to form an online community to advance translation work. We will review the resources now available in Spanish, discuss the complexity of having an inclusive text for all Spanish speaking countries, outline plans for future updates and explain how you can become a part of the MuseumPests en Español community.

FUNdamentals of Museum IPM Now Available

Christa Deacy-Quinn, Spurlock Museum

At MuseumPests 2019 I presented my outline for FUNdamentals of Museum IPM, was grateful for feedback and encouragement from members of MuseumPests to write my book. Thanks to a generous grant from the North Central IPM Center, I have published a book, FUNdamentals of Museum IPM, intended for museums without professional IPM staff members. It is distributed free to those requesting it. Since it became available in December 2019, over 325 hard copies have been requested and sent to museums and the pdf version available free online has been downloaded over 672 times by heritage-collecting institutions from over 48 countries.

Fur, Four Legs and a Tail: Update from the MuseumPests Rodent group

MuseumPests Rodent Group

The “Rodent Group” subcommittee of the MuseumPests Working Group has been gathering information on rodent pests during the last few working meetings. We are ready to share the new Rodent Resources! This presentation will walk through all the important information that IPM folks should know regarding identifying and mitigating a mouse and rat problem – and where to find that information on the website.

The Risk of Pests in Monasteries

Ann Shaftel

Pests are a significant and ongoing threat in monasteries in many parts of the world. Risk assessment is crucial for prevention of damage to Buddhist sacred art in monasteries and communities. This short talk introduces the Pests chapter from Preservation of Buddhist Treasures Resource, which is available free and online. Risk categories are refined for the monastic context where these risks are encountered daily, this is not an educational exercise. The Pest situations come directly from the monks and nuns in their own words (translated to English for this talk), and illustrated with images from within monasteries. Practical and low-cost solutions as taught in Treasure Caretaker Training preservation workshops are offered in this chapter about Pests, which was throughly reviewed by expert Louis Sorkin.

Pest Odyssey2021 – The Next Generation

Suzanne Ryder, The Natural History Museum London

Learn more about the Pest Odyssey virtual conference being held in September 2021.

DATA MANAGEMENT & REPORTING

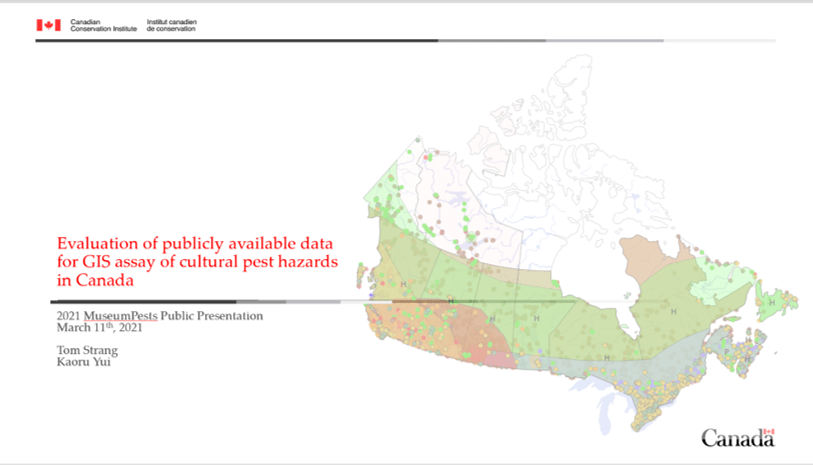

Evaluation of publicly available data for GIS assay of cultural pest hazards in Canada

Tom Strang and Kaoru Yui, Canadian Conservation Institute

There is continual growth in significant publicly available digital and landmark print published checklist data on the distribution of pests of concern for the protection of cultural property. For a recent CCI workshop, the authors revised CCI’s understanding of pest distribution from these improving public sources. The visualization of data through a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) approach is fairly straightforward through such mechanisms as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) data portal. GBIF datasets provide specimen data including location and date at useful levels of systematic detail for constructing a national picture. Checklists were inspected for species of concern and imported into GIS data formats that provide confirmation of provincial incidence. This effort illustrated both richness in detail and likely voids in the datasets. With the growth of citizen science, there are means for interested parties to enrich the dataset through readily available mechanisms such as iNaturalist.org research grade identifications that are discoverable through GBIF distribution datasets. Combining with CCI’s initiative in GIS of Canada’s cultural heritage organizations allows CCI to examine aggregate or specific pest hazards for our client organizations along with other risks.

Communicating conservation data. Example: IPM data

Jane Henderson, Cardiff University and Christian Baars, National Museums Liverpool

Many conservation practices require the collection and generation of data. Conservation data are not generated purely in their own right; instead, data are needed to deliver outcomes such as evaluating the effectiveness of conservation processes, or providing reassurance to internal or external stakeholders. Data collection and communication have limitations which become especially apparent when data are presented. IPM data, in particular, illustrate the potential for introducing confirmation bias following patterns of placement of insect pest monitors. This presentation examines the outcomes being sought from using IPM and asks whether the data collection and presentation currently offered are a good fit. Many IPM research questions identify dynamic challenges, such as the migration of a new pest through a country, or the spread of an established pest within a collection but data representation is less well suited to dynamic change. The presentation proposes that a greater focus on the needs of the audience and the goal of data presentation will generate an effective range of approaches for peers, technical experts, colleagues and decision makers. To resolve this, this presentation recommends a fundamental change to the way IPM data are collected and presented, using standardisation of data collection and a consideration of user needs in presenting the findings, including effective forms of visualisation.

Analysing and presenting pest occurrence data

Christian Baars, National Museums Liverpool and Jane Henderson, Cardiff University

There are many tools assisting preventive conservators and pest managers in monitoring and identifying pests. This generates a considerable amount of data which are recorded in various ways, forming one essential element of Integrated Pest Management (IPM). We have reviewed the outcomes being sought from pest monitoring – management buy-in, better resourcing of preventive conservation, improvements to collections care – and whether data analysis and presentation currently offer the necessary tools to achieve these. This especially considers poorly-resourced institutions without access to specialist software. We propose a greater focus on the needs of the target audiences of pest management messaging, highlighting the importance of introducing standardised data collection, appropriate data analysing, and consideration of user needs when presenting findings. One crucial aspect is the way data are analysed: presenting pest data in relation to either floor area or number of pest traps introduces unintended biases which may skew interpretation. For this reason, we have proposed the use of a Pest Occurrence Index (POI) which is a function of the pest count, floor area and the number of pest monitors as well as the length of time pest monitors are exposed between pest counts, as all of these affect the number of pests caught in a defined space. This presentation explains the development of the POI and outlines the benefits of calculating POI and presenting standardised pest monitoring findings in a way that removes unintended bias.

Development of the Collection Pest Database and Pest Occurrence Database

Melissa King, Austin Senseman and Nathan McMinn, Conserv

MuseumPests and Conserv are collaborating on two projects to promote the preservation community’s long-term research efforts into IPM. As the team at Conserv initiated development of freely available collections-focused IPM software, they realized a need for a searchable database of pests that include quantifiable variables such as diet, preferred environment, seasonal life cycle habits, geographic location, and more. Conserv is working with MuseumPests Working Group participants to create the “Collection Pest Database” (CPDB), which will be publicly available for data science research. Both organizations also saw the value of combining user-input IPM datasets entered into the software over time. This “Pest Occurrence Database” (PODB), will be an anonymized dataset of observations used to track seasonal and geographic trends and to establish IPM baselines for collections. Users entering data into the IPM software will be addressing their individual collection challenges while also effortlessly contributing to a rich dataset for future academic research. Transitioning from siloed IPM spreadsheet solutions to a big data structure will empower the field to use artificial intelligence and machine learning processes to develop predictive models for classification and infestation. These new models integrated with environmental datasets hold the promise for a more complete understanding of pests in collections.

At-A-Glance Reports for IPM Data

Morgan Nau, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology

In an effort to move away from long reports with text and data that people would not read through, The Peabody Museum’s IPM reports are now 1-2 pages and feature color coded graphs, pie charts, and minimal text. This at-a-glance report has made it easier to demonstrate problems to a wide variety of people from directors to building managers to individual departments, and has led to very positive feedback from museum administration.

INSECT BEHAVIOR

Genetic variability of Gray Silverfish Ctenolepisma longicaudata and Ghost Silverfish C. calva in infested collections worldwide

Bill Landsberger, Rathgen Research Laboratory

The Gray Silverfish Ctenolepisma longicaudata Escherich, 1905 is an invasive and seriously dangerous insect pest in museums, archives and libraries. At temperate climates in the middle latitudes, C. longicaudata is cosmopolitan and synanthropic, dependent on indoor conditions. Its natural origin and habitats are still unknown. The Gray Silverfish has been common in North America and Australia already since at least the 1930s, but it only became introduced to and rapidly spread in Central Europe within the last ten years. Another lepismatid species, the Ghost Silverfish Ctenolepisma calva (Ritter, 1910) has also been found in this region during the last five years in collection storage areas, often associated with C. longicaudata. In an ongoing research project the genetic variability of these invasive pest species will be studied in samples from a large number of infested collections and in specimens preserved in natural history collections worldwide. Patterns of genetic differentiation in the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene as the standard metazoan DNA barcoding marker will be used to elucidate our understanding of the potential distribution routes of these pests and to obtain information on their likely geographical areas of origin, which could help to identify natural biological control agents.

Native woods and their resistance to pest attack in heritage buildings

Yerko Quitral, Museum of Chemistry and Pharmacy, University of Chile

The resistance of some species of wood has been described as part of the biological mechanism of some native plants to resist degradation by insects, fungi and also acclimatization to extreme climates, such as wind and constant rain. This resistance or sensitivity to the physical and chemical degradation of wood is a relevant trait to know in heritage buildings and museums, historical house and artistic collections. The study has characterized the wood species present in the building corresponding to the Museum of Chemistry and Pharmacy of the University of Chile, in Santiago de Chile, which dates from 1900 and corresponds to a series of small palaces built in an emerging capital with mostly native materials, such as endemic tree species from south of Chile. As part of the study of the state of conservation of the building, the structural and ornamental wood species, the identification of areas with intervention and the association with the presence of active and inactive pests in the growth period have been characterized. Active pests of Woodworms (Anobium punctatum) were found in the building, in woods characterized as sensitive and used in remodeling interventions without conservation criteria. Cleaning, disinsection and monitoring protocols are carried out in a relevant area of the building for its stabilization. Knowledge of the wood species that exist in a building is important to develop adapted preservation and conservation plans, as well as the understanding of a correct intervention.

TREATMENT

Implementation of New Nitrogen-Based Anoxic Systems at Historic New England

Adam Osgood, Historic New England, Patrick Kelley, Insects Limited and Bill Smith, Heritage Packaging

Historic New England is a 110-year-old regional historic preservation organization with 38 historic house museum sites in the northeastern United States. Many of these sites are fully furnished with furniture made from wood or animal fibers. Very few of the sites have modern climate control and pest issues are a regular challenge. Part of the on-going IPM program includes the use of a 1,000 cubic foot Controlled Atmosphere Facility or “Bubble”, which uses a reusable PVC membrane and CO2 to displace the existing atmosphere in order to remediate pests. Historic New England has been operating this facility for internal use and providing treatment services to outside clients safely, and effectively for nearly 30 years. In the spring of 2020, the current system showed signs that the PVC membrane was degrading. An increased consumption of CO2 was needed to maintain the required levels for treatment and the system was becoming less efficient to run. In looking at new technologies in design that are available, it was determined that the construction and design of a controlled atmosphere facility using nitrogen rather than CO2 at the same scale is now possible. With the use of a nitrogen generator, as well as a custom humidification system and a custom, portable “Bubble” enclosure, Historic New England can provide a system that is more financially and environmentally sustainable. This presentation will discuss the financial hurdles and practical obstacles leading up to this decision of conversion to nitrogen as an anoxic treatment. It will also outline the engineering, design and technical components of the new facility that is currently under construction.

On-boarding an IPM freezer – a brief update

Eric Breitung and Michael Millican, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Met’s freezer was installed by the time the 2020 MuseumPests meeting started, but it’s only now, a year later, becoming operational. This presentation will cover the freezer’s basic specifications and start-up timeline, including a range of snags and successes. Once running, the freezer’s temperature uniformity, low-temperature point, and time required to reach low temperatures were tested and compared to the design specifications. Surrogates for both textile and wood artifacts were produced as well to understand the time required for art to reach low temperatures and return to room temperature. Other testing being planned will be outlined including the introduction to the freezer of mixed media materials that are sometimes found on historical textiles with the goal of determining whether condensation or macro-scale damage occurs. Finally, as we near having a fully operational system, the policies and procedures for how the museum will operate the freezer and its pre- and post-treatment spaces are being developed by a wide range of interested departments. These will be briefly mentioned as well.

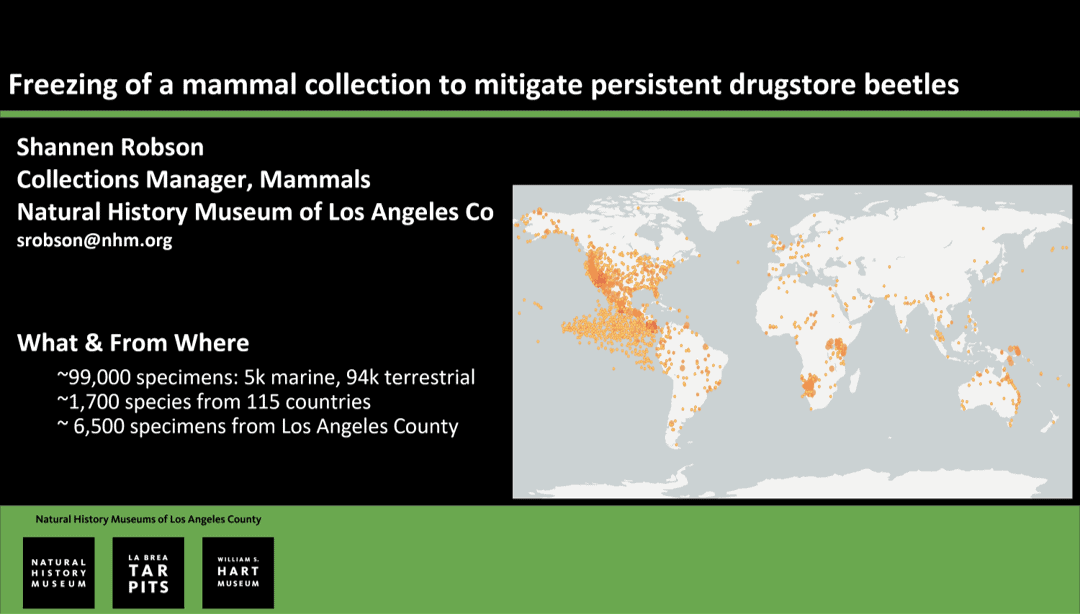

Freezing of a mammal collection to mitigate persistent drugstore beetles

Shannen Robson, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County mammal collection is the 14th largest in North America with nearly 100,000 specimens from around the world. The majority of these specimens are stored in the primary NHM building and have experienced a persistent drugstore beetle infestation for over a decade. Years of various IPM deterrents – pheromone traps, silica dust, spot freezing, and containment – have failed to resolve the issue. In early 2020, NHM mammal staff and conservators coordinated a plan to pack and freeze the collection over several months in a 40′ freezer container, then reinstall after cabinets and wooden drawers were cleaned and chemically treated. The treatment steps have been successfully completed and reinstallation is now underway. Project challenges included the packing of various preparation types, tracking of specimens and boxes, the sudden reduction in staff and volunteers during COVID restrictions, remote temperature tracking, and the sharing of storage space with other departments.